The President, motivator-in-chief

Presidential character

The good heart transcends all notions of a political 'left' and 'right', and a sincere, compassionate leader can impart regeneration of a nation through words, as well as constructive deeds appropriate to the age. Such regeneration can be associated with ideals and values that all mainstream political and religious groups can relate to, whether one is a conservative christian or a liberal humanist. By values, I mean humanitarian love, honesty, patience, and tolerance - all of which are rooted in the individual citizen.

I will offer two examples of American Presidents whose words carried a sense of love and power, leaders whose words uplifted and assured, encouraged and didn't condemn, even if a universal conclusion on their policies is never likely to be reached.

Roosevelt remembered

One of the most important aspects of Presidential leadership is to maintain or cultivate the nation's spiritual morale. Historically, this has clearly been a factor in Presidential success, or at least, perceived success. This can be done through showing the sincerity of election promises by putting into action those pledges, but something more is needed than appropriate policy prescriptions. To be a successful leader, the President needs to inspire his people to good. This is more a spiritual, than a political, requirement.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, President of the United States from 1933-1945 is respected by the majority of modern day Americans, for the character of his leadership. This is demonstrated by the fact that conservatives, and not only liberals, continue to pay tribute to FDR, whose New Deal programes were unravelled during the conservative revolution of the 1980s. Ronald Reagan himself, the architect of that revolution, preferred to cloak his opposition to big government in terms of President Lyndon Baines Johnson's "great society" platform than be seen to oppose FDR's New Deal. Yet this is not an inconsistency, if we consider the primary responsibility of leadership to be the communication of comfort, hope, and aspiration.

Such a leader must be the leader of the whole country, and be viewed as such, rather than as the leader of a particular political party. The ultimate responsibility for imparting the noble ends of individual self-government, unselfish patriotism, and comfort and security lie within the leader's own capacity for encouraging citizens to imbibe themselves with these aspects.

FDR was a great leader. His assurance to his people that "we have nothing to fear but fear itself", his fireside chats, and his strong committment to the poor, all during a tumultous and uncertain era, are indicative of this President's compassionate spirit. The fact that his 'collectivist' experiments were later discredited matter not when we consider his impact on the spiritual morale of the nation at that time, demonstated by the volume of letters he received in gratitude for his help. Roosevelt will always be thought of fondly for the spirit of compassion that went into his programmes.

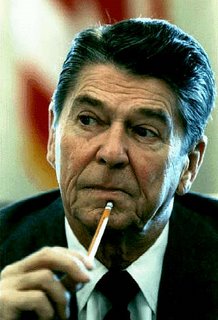

Ronald Wilson Reagan

Ronald Reagan, like FDR decades before, came to power at a time of deep economic malaise. America's spiritual resurgence in the 1980s depended, most of all, on a change in perspective, and this was imparted by Reagan's central message - American's had a right to love themselves again. Now, there is much healthy scepticism about that last point, but I believe that Reagan's speeches genuinely made people "feel good" about themselves again. Critics would argue that I speak of his words, and not his actions, yet do not words, when spoken sincerely and with genuine love, impart reassurance and thus contain a power to heal?

Reagan's first inaugural address, in 1981, set the tone for how the American President can not only be the nation's commander-in-chief, but the motivator-in-chief as well. After expressing gratitude to President Carter for the orderly transition period, Reagan went on to celebrate the heroes of America, the 250 million citizens from every walk of life. The purpose of the speech must have been to encourage individual American idealism; to alert citizens to helping themselves and each other through their own human capacities. Reagan asked 'how can we love our country and not love our countrymen;' and imbibed a spirit of unselfish patriotism consistent with JFK's 'ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country'. The spirit of the speech must have touched viewers and listeners, and been the seed of the more optimistic decade that was to ensue.

Concluding thought

The President's individual qualities will have an impact on the nation as a whole. In addition to sound policy, whatever that might be, the health of national feeling depends on communicative leaders whose words encourage the the civic righteousness and moral goodness of citizens.